What were the Bob Damron Address Books?

Figure 1. Cover of the 1986 edition of Bob Damron's Address Book.

While operating one of his many gay bars in the 1960s, Bob Damron started a side project publishing gay travel guides that featured bars like his. Called the Bob Damron Address Books, these guides proved popular and became a valuable resource for gay travelers looking for friends, companions, and safety. First published in an era when most states banned same-sex intimacy both in public and private spaces, these travel guides helped gays (and to a lesser extent, lesbians) find bars, cocktail lounges, bookstores, restaurants, bathhouses, cinemas, and cruising grounds that catered to people like themselves.

Much like the Green Books of the 1950s and 1960s, used by African Americans used to find friendly businesses that would serve them in the era of Jim Crow apartheid, Damron’s guidebooks aided a generation of queer people in identifying sites of community, pleasure, and politics. They made visible a queer geography that was otherwise difficult, and often dangerous, to navigate.

Damron’s guidebooks were part of a growing surge in gay travel guide publications that began in the early 1960s. Bob Damron wasn’t the only entrepreneur looking to offer gay consumers listings of queer friendly places. Guy Strait published the first edition of The Lavender Baedeker in 1963, an extension to his already popular newspaper in San Francisco entitled Citizen’s Guide. Other publications soon followed, including Guild Guide to the Gay Scene and World Report Travel Guide, published not in the gay mecca of San Francisco but rather in New York. Despite stiff competition from these early publishers and later “copycats” (as Damron often described them), Damron’s guidebooks were perhaps the most extensive and long running of any of the early gay travel guides. In fact, unlike all his initial competition, Damron’s guides lasted until the early 2020s. While the internet age ultimately contributed to the downfall of the guides (with much of the guidebook’s information inside easily accessible on the web for free), it’s worth highlighting that the Bob Damron Address Books existed for nearly six decades. It suggests an enduring and active queer travel community that never was strictly confined to a closet.

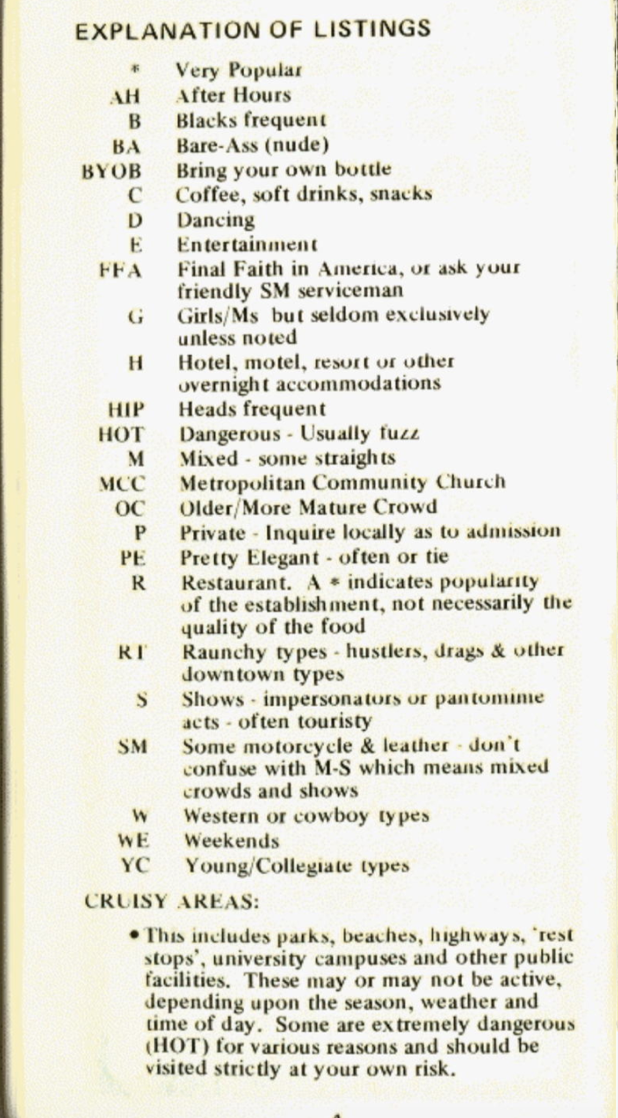

Figure 2. Explanation of Listings in the 1976 edition of Bob Damron's Address Book. In our data, we refer to these categories as "Amenity Features."

To be sure, Damron’s guides are not a perfect historical source. Since these guides were aimed mostly at gay men, they overlook large swaths of queer culture. Little in the pages of Damron offers insight into the vibrant culture of trans people, for example, at least until the later 1990s. In addition, Bob Damron’s Address Books largely understand the gay world from the perspective of a San Franciscan, white gay man. The early guides often reflect coastal biases, seeing places outside the queer meccas of New York or San Francisco as almost primitive. Even so, the Damron guidebooks remain one of the most extensive and geographically diverse records of queer social space available for the mid to late twentieth century.

Mapping the Gay Guides believes that mapping Damron’s guidebooks can offer valuable insight into the queer world beginning in the 1960s. Our research team has begun turning the tens of thousands of listings within the guides into usable, functioning data to allow researchers to make connections between historical queer communities. Mapping this data allows us to display the distribution of locations and explore the growth of the queer communities over time. In the U.S. South, for example, you can explore 154 queer spots across twelve states in 1965 to over a thousand locations in those same states by 1980.

Damron’s use of letters and symbols to describe the features of gay spaces, such as racial minorities (“B” for “Blacks frequent,” for example), entertainment, or risk, adds another layer of historical meaning, allowing users to navigate through nuances in queer geography. Mapping the Gay Guides turns the incredible textual documents of gay travel guides into accessible visualizations, useful in exploring change and continuity in American queer communities over time.

We believe the stake of this project are high. The vast majority of venues listed in the early decades of the Damron Address Books no longer exist. Little remains of the queer world found in the pages within the Damron Address Books that began in 1964. In addition, since queer businesses like bars or bathhouses or the informal nature of cruising locations often leave few historical records, the queer history of local communities can often seem invisible or nonexistent. Mapping the Gay Guides intends to counter this form of cultural erasure of historical geography by making visible the places where queer people actively sought and found places of acceptance for decades, even in places regarded as homophobic, hostile, or indifferent.